Hi all,

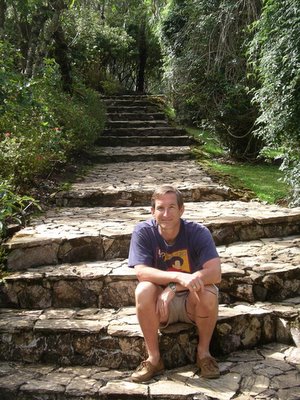

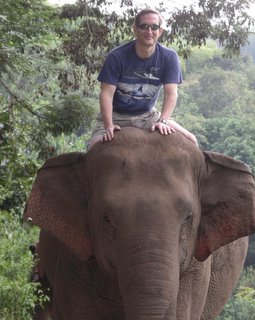

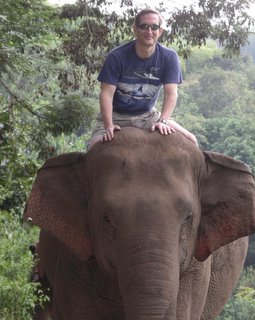

What a week (10 days actually)! I’m just now returning from my first trip to Thailand, where I visited my friend and new-found traveling companion Dan, and we spent our time up north in Chiang Rei. Wow! It was absolutely unbelievable. I will write more about that later. And pictures? I only took 900 of them, so my challenge will be picking out the few worth sharing.

OK, enough of my vacation (which, by the way, was really quite spiritual). You may have noticed that this post comes to you from a new blog: my “Just Un-Do It” blog, which refers to my counter-cultural message (that my family knows all too well). All we really need to do is “Un-Do” the various indoctrinations (be they cultural, social, familial, or even inherited, and certainly, un-do the media messages by which we are accosted).

As my first post to this new forum, I’m including, in its entirety, an article from Ken Wilbur, I believe taken out of the magazine “What is Enlightenment?” I have recommended that magazine before, and you can find the link over at the “other” blog:

http://hi-seekers.blogspot.com/

(I’m hoping that acknowledgement and pointer will mollify the copyright police ;-)

This article puts in black and white many of the issues that have gotten under my skin, especially the relationship of religion to spirituality or a higher truth. It also raises the seeker conundrum (to seek or not to seek). And it is put so succinctly, and to me rings very true. I hope you find it provocative as well as insightful. I very much enjoyed it.

I welcome and encourage feedback, and request you post your comments on the blog so others (not necessarily on this list) can benefit from them:

http://justun-doit.blogspot.com/

To non-seeking ... “Just un-do it!”

S-

p.s., and to those of you that are tired of my “long” posts, all I can say is “sorry”. Read it when you are “in the mood”.

=======

A Spirituality that Transforms

by Ken Wilber

Ken Wilber needs little introduction. A genius recognized in his own time, this prolific author is widely acclaimed for his innovative and critical synthesis of philosophies East and West, and has been hailed by many as one of the brightest lights of the modern spiritual world. With an ever growing influence, his ideas claim adherents from an enormous diversity of ideological camps—while he, a practicing Buddhist, remains fiercely independent, aligned only to the force of his own inquiry. Not afraid to take the risk of being controversial, he has been harshly criticized for his outspoken and fearless questioning of many of the most cherished ideas of the modern progressive status quo.

Yet it is this very quality in him, his unrelenting passion for genuine inquiry—a quality all too rare in the modern spiritual arena—that we find so refreshing. In the following original essay Ken Wilber shouts from his heart, imploring each of us to take up the challenge of embracing "a spirituality that transforms."Hal Blacker, a contributing editor for What Is Enlightenment?, has described the topic of this special issue of the magazine in the following way (although this repeats statements made elsewhere in this issue, it is nonetheless worth quoting at length, simply because of its eloquence, straightforwardness, and unerring good sense):

We intend to explore a sensitive question, but one which needs to be addressed—the superficiality that pervades so much of the current spiritual exploration and discourse in the West, particularly in the United States. All too often, in the translation of the mystical traditions from the East (and elsewhere) into the American idiom, their profound depth is flattened out, their radical demand is diluted, and their potential for revolutionary transformation is squelched. How this occurs often seems to be subtle, since the words of the teachings are often the same. Yet through an apparent sleight of hand involving, perhaps, their context and therefore ultimately their meaning, the message of the greatest teachings often seems to become transmuted from the roar of the fire of liberation into something more closely resembling the soothing burble of a California hot tub. While there are exceptions, the radical implications of the greatest teachings are thereby often lost. We wish to investigate this dilution of spirituality in the West and inquire into its causes and consequences.

I would like to take that statement and unpack its basic points, commenting on them as best I can, because taken together, those points highlight the very heart and soul of a crisis in American spirituality.

—K.W.

TRANSLATION VS. TRANSFORMATION

In a series of books (e.g., A Sociable God, Up from Eden, and The Eye of Spirit), I have tried to show that religion itself has always performed two very important, but very different, functions. One, it acts as a way of creating meaning for the separate self: it offers myths and stories and tales and narratives and rituals and revivals that, taken together, help the separate self make sense of, and endure, the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. This function of religion does not usually or necessarily change the level of consciousness in a person; it does not deliver radical transformation. Nor does it deliver a shattering liberation from the separate self altogether. Rather, it consoles the self, fortifies the self, defends the self, promotes the self. As long as the separate self believes the myths, performs the rituals, mouths the prayers, or embraces the dogma, then the self, it is fervently believed, will be "saved"—either now in the glory of being God-saved or Goddess-favored, or in an afterlife that insures eternal wonderment.

But two, religion has also served—in a usually very, very small minority— the function of radical transformation and liberation. This function of religion does not fortify the separate self, but utterly shatters it—not consolation but devastation, not entrenchment but emptiness, not complacency but explosion, not comfort but revolution—in short, not a conventional bolstering of consciousness but a radical transmutation and transformation at the deepest seat of consciousness itself.

There are several different ways that we can state these two important functions of religion. The first function—that of creating meaning for the self—is a type of horizontal movement; the second function—that of transcending the self—is a type of vertical movement (higher or deeper, depending on your metaphor). The first I have named "translation," the second, "transformation."

With translation, the self is simply given a new way to think or feel about reality. The self is given a new belief—perhaps holistic instead of atomistic, perhaps forgiveness instead of blame, perhaps relational instead of analytic. The self then learns to translate its world and its being in the terms of this new belief or new language or new paradigm, and this new and enchanting translation acts, at least temporarily, to alleviate or diminish the terror inherent in the heart of the separate self.

But with transformation, the very process of translation itself is challenged, witnessed, undermined and eventually dismantled. With typical translation, the self (or subject) is given a new way to think about the world (or objects); but with radical transformation, the self itself is inquired into, looked into, grabbed by its throat and literally throttled to death.

Put it one last way: with horizontal translation—which is by far the most prevalent, widespread and widely shared function of religion—the self is, at least temporarily, made happy in its grasping, made content in its enslavement, made complacent in the face of the screaming terror that is in fact its innermost condition. With translation, the self goes sleepy into the world, stumbles numbed and nearsighted into the nightmare of samsara, is given a map laced with morphine with which to face the world. And this, indeed, is the common condition of a religious humanity, precisely the condition that the radical or transformative spiritual realizers have come to challenge and to finally undo.

For authentic transformation is not a matter of belief but of the death of the believer; not a matter of translating the world but of transforming the world; not a matter of finding solace but of finding infinity on the other side of death. The self is not made content; the self is made toast.

Now, although I have obviously been favoring transformation and belittling translation, the fact is that, on the whole, both of these functions are incredibly important and altogether indispensable. Individuals are not, for the most part, born enlightened. They are born in a world of sin and suffering, hope and fear, desire and despair. They are born as a self ready

and eager to contract; a self rife with hunger, thirst, tears and terror. And they begin, quite early on, to learn various ways to translate their world, to make sense of it, to give meaning to it, and to defend themselves against the terror and the torture never lurking far beneath the happy surface of the separate self.

And as much as we, as you and I, might wish to transcend mere translation and find an authentic transformation, nonetheless translation itself is an absolutely necessary and crucial function for the greater part of our lives. Those who cannot translate adequately, with a fair amount of integrity and accuracy, fall quickly into severe neurosis or even psychosis: the world ceases to make sense—the boundaries between the self and the world are not transcended but instead begin to crumble. This is not breakthrough but breakdown; not transcendence, but disaster.

But at some point in our maturation process, translation itself, no matter how adequate or confident, simply ceases to console. No new beliefs, no new paradigm, no new myths, no new ideas, will staunch the encroaching anguish. Not a new belief for the self, but the transcendence of the self altogether, is the only path that avails.

Still, the number of individuals who are ready for such a path is, always has been, and likely always will be, a very small minority. For most people, any sort of religious belief will fall instead into the category of consolation: it will be a new horizontal translation that fashions some sort of meaning in the midst of the monstrous world. And religion has always served, for the most part, this first function, and served it well.

I therefore also use the word "legitimacy" to describe this first function (the horizontal translation and creation of meaning for the separate self). And much of religion's important service is to provide legitimacy to the self— legitimacy to its beliefs, its paradigms, its worldviews and its way in the world. This function of religion to provide a legitimacy for the self and its

beliefs—no matter how temporary, relative, nontransformative, or illusory— has nonetheless been the single greatest and most important function of the world's religious traditions. The capacity of a religion to provide horizontal meaning, legitimacy and sanction for the self and its beliefs—that function of religion has historically been the single greatest "social glue" that any culture has.

And one does not tamper easily, or lightly, with the basic glue that holds societies together. Because more often than not, when that glue dissolves— when that translation dissolves—the result, as we were saying, is not breakthrough but breakdown, not liberation but social chaos. (We will return to this crucial point in a moment.)

Where translative religion offers legitimacy, transformative religion offers authenticity. For those few individuals who are ready—that is, sick with the suffering of the separate self, and no longer able to embrace the legitimate worldview—a transformative opening to true authenticity, true enlightenment, true liberation, calls more and more insistently. And, depending upon your capacity for suffering, you will sooner or later answer the call of authenticity, of transformation, of liberation on the lost horizon of infinity.

Transformative spirituality does not seek to bolster or legitimate any present worldview at all, but rather to provide true authenticity by shattering what the world takes as legitimate. Legitimate consciousness is sanctioned by the consensus, adopted by the herd mentality, embraced by the culture and the counterculture both, promoted by the separate self as the way to make sense of this world. But authentic consciousness quickly shakes all of that off its back, and settles instead into a glance that sees only a radiant infinity in the heart of all souls and breathes into its lungs only the atmosphere of an eternity too simple to believe.

Transformative spirituality, authentic spirituality, is therefore revolutionary. It does not legitimate the world, it breaks the world; it does not console the world, it shatters it. And it does not render the self content, it renders it undone.

And those facts lead to several conclusions.

WHO ACTUALLY WANTS TO TRANSFORM?

It is a fairly common belief that the East is simply awash in transformative and authentic spirituality, but that the West—both historically and in today's "New Age"—has nothing much more than various types of horizontal, translative, merely legitimate and therefore tepid spirituality. And while there is some truth to that, the actual situation is much gloomier, for both the East and the West alike.

First, although it is generally true that the East has produced a greater number of authentic realizers, nonetheless, the actual percentage of the Eastern population that is engaged in authentic transformative spirituality is, and always has been, pitifully small. I once asked Katigiri Roshi, with whom I had my first breakthrough (hopefully, not a breakdown), how many truly great Ch'an and Zen masters there have historically been. Without hesitating, he said, "Maybe one thousand altogether." I asked another Zen master how many truly enlightened—deeply enlightened—Japanese Zen masters there were alive today, and he said, "Not more than a dozen."

Let us simply assume, for the sake of argument, that those are vaguely accurate answers. Run the numbers. Even if we say there were only one billion Chinese over the course of its history (an extremely low estimate), that still means that only one thousand out of one billion had graduated into an authentic, transformative spirituality. For those of you without a calculator, that's 0.0000001 of the total population.

And that means, unmistakably, that the rest of the population were (and are) involved in, at best, various types of horizontal, translative, merely legitimate religion: they were involved in magical practices, mythical beliefs, egoic petitionary prayer, magical rituals, and so on—in other words, translative ways to give meaning to the separate self, a translative function that was, as we were saying, the major social glue of the Chinese (and all other) cultures to date.

Thus, without in any way belittling the truly stunning contributions of the glorious Eastern traditions, the point is fairly straightforward: radical transformative spirituality is extremely rare, anywhere in history, and anywhere in the world. (The numbers for the West are even more depressing. I rest my case.)

So, although we can very rightly lament the very small number of individuals in the West who are today involved in a truly authentic and radically transformative spiritual realization, let us not make the false argument of claiming that it has otherwise been dramatically different in earlier times or in different cultures. It has on occasion been a little better than we see here, now, in the West, but the fact remains: authentic spirituality is an incredibly rare bird, anywhere, at any time, at any place. So let us start from the unarguable fact that vertical, transformative, authentic spirituality is one of the most precious jewels in the entire human tradition—precisely because, like all precious jewels, it is incredibly rare.

Second, even though you and I might deeply believe that the most important function we can perform is to offer authentic transformative spirituality, the fact is, much of what we have to do, in our capacity to bring decent spirituality into the world, is actually to offer more benign and helpful modes of translation. In other words, even if we ourselves are practicing, or offering, authentic transformative spirituality, nonetheless much of what we must first do is provide most people with a more adequate way to translate their condition. We must start with helpful translations before we can effectively offer authentic transformations.

The reason is that if translation is too quickly, or too abruptly, or too ineptly taken away from an individual (or a culture), the result, once again, is not breakthrough but breakdown, not release but collapse. Let me give two quick examples here.

When Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a great (though controversial) Tibetan master, first came to this country, he was renowned for always saying, when asked the meaning of Vajrayana, "There is only Ati." In other words, there is only the enlightened mind wherever you look. The ego, samsara, maya and illusion—all of them do not have to be gotten rid of, because none of them actually exist: There is only Ati, there is only Spirit, there is only God, there is only nondual Consciousness anywhere in existence.

Virtually nobody got it—nobody was ready for this radical and authentic realization of always-already truth—and so Trungpa eventually introduced a whole series of "lesser" practices leading up to this radical and ultimate "no practice." He introduced the Nine Yanas as the foundation of practice—in other words, he introduced nine stages or levels of practice, culminating in the ultimate "no practice" of always-already Ati.

Many of these practices were simply translative, and some were what we might call "lesser transformative" practices: miniature transformations that made the bodymind more susceptible to radical, already-accomplished enlightenment. These translative and lesser practices issued forth in the "perfect practice" of no-practice—or the radical, instantaneous, authentic realization that, from the very beginning, there is only Ati. So even though ultimate transformation was the prior goal and ever-present ground, Trungpa had to introduce translative and lesser practices in order to prepare people for the obviousness of what is.

Exactly the same thing happened with Adi Da, another influential (and equally controversial) adept (although this time, American-born). He originally taught nothing but "the path of understanding": not a way to attain enlightenment, but an inquiry into why you want to attain enlightenment in the first place. The very desire to seek enlightenment is in fact nothing but the grasping tendency of the ego itself, and thus the very search for enlightenment prevents it. The "perfect practice" is therefore not to search for enlightenment, but to inquire into the motive for seeking itself. You obviously seek in order to avoid the present, and yet the present alone holds the answer: to seek forever is to miss the point forever. You always already ARE enlightened Spirit, and therefore to seek Spirit is simply to deny Spirit. You can no more attain Spirit than you can attain your feet or acquire your lungs.

Nobody got it. And so Adi Da, exactly like Trungpa, introduced a whole series of translative and lesser transformative practices—seven stages of practice, in fact—leading up to the point that you could dispense with seeking altogether, there to stand open to the always-already truth of your own eternal and timeless condition, which was completely and totally present from the start, but which was brutally ignored in the frenzied desire to seek.

Now, whatever you might think of those two adepts, the fact remains: they performed perhaps the first two great experiments in this country on how to introduce the notion that "There is only Ati"—there is only Spirit—and thus seeking Spirit is exactly that which prevents realization. And they both found that, however much we might be alive to Ati, alive to the radical transformative truth of this moment, nonetheless, translative and lesser transformative practices are almost always a prerequisite for that final and ultimate transformation.

My second point, then, is that in addition to offering authentic and radical transformation, we must still be sensitive to, and caring of, the numerous beneficial modes of lesser and translative practices. This more generous stance therefore calls for an "integral approach" to overall transformation, an approach that honors and incorporates many lesser transformative and

translative practices—covering the physical, emotional, mental, cultural and communal aspects of the human being—in preparation for, and as an expression of, the ultimate transformation into the always-already present state.

And so, even as we rightly criticize merely translative religion (and all the lesser forms of transformation), let us also realize that an integral approach to spirituality combines the best of horizontal and vertical, translative and transformative, legitimate and authentic—and thus let us focus our efforts on a balanced and sane overview of the human situation.

WISDOM AND COMPASSION

But isn't this view of mine terribly elitist? Good heavens, I hope so. When you go to a basketball game, do you want to see me or Michael Jordan play basketball? When you listen to pop music, who are you willing to pay money in order to hear? Me or Bruce Springsteen? When you read great literature, who would you rather spend an evening reading, me or Tolstoy? When you pay $64 million for a painting, will that be a painting by me or by Van Gogh?

All excellence is elitist. And that includes spiritual excellence as well. But spiritual excellence is an elitism to which all are invited. We go first to the great masters —to Padmasambhava, to St. Teresa of Avila, to Gautama Buddha, to Lady Tsogyal, to Emerson, Eckhart, Maimonides, Shankara, Sri Ramana Maharshi, Bodhidharma, Garab Dorje. But their message is always the same: let this consciousness be in you that is in me. You start elitist, always; you end up egalitarian, always.

But in between, there is the angry wisdom that shouts from the heart: we must, all of us, keep our eye on the radical and ultimate transformative goal. And so any sort of integral or authentic spirituality will also, always, involve a critical, intense and occasionally polemical shout from the transformative camp to the merely translative camp.

If we use the percentages of Chinese Ch'an as a simple blanket example, this means that if 0.0000001 of the population is actually involved in genuine or authentic spirituality, then .99999999 of the population is involved in nontransformative, nonauthentic, merely translative or horizontal belief systems. And that means, yes, that the vast, vast majority of "spiritual seekers" in this country (as elsewhere) are involved in much less-than-authentic occasions. It has always been so; it is still so now. This country is no exception.

But in today's America, this is much more disturbing, because this vast majority of horizontal spiritual adherents often claim to be representing the leading edge of spiritual transformation, the "new paradigm" that will change the world, the "great transformation" of which they are the vanguard. But more often than not, they are not deeply transformative at all; they are merely, but aggressively, translative—they do not offer effective means to utterly dismantle the self, but merely ways for the self to think differently. Not ways to transform, but merely new ways to translate. In fact, what most of them offer is not a practice or a series of practices, not sadhana or satsang or shikan-taza or yoga. What most of them offer is simply the suggestion: read my book on the new paradigm. This is deeply disturbed, and deeply disturbing.

Thus, the authentic spiritual camps have the heart and soul of the great transformative traditions, and yet they will always do two things at once: appreciate and engage the lesser and translative practices (upon which their own successes usually depend), but also issue a thundering shout from the heart that translation alone is not enough.

And therefore, all of those for whom authentic transformation has deeply unseated their souls must, I believe, wrestle with the profound moral obligation to shout from the heart—perhaps quietly and gently, with tears of reluctance; perhaps with fierce fire and angry wisdom; perhaps with slow and careful analysis; perhaps by unshakable public example—but authenticity always and absolutely carries a demand and duty: you must speak out, to the best of your ability, and shake the spiritual tree, and shine your headlights into the eyes of the complacent. You must let that radical realization rumble through your veins and rattle those around you.

Alas, if you fail to do so, you are betraying your own authenticity. You are hiding your true estate. You don't want to upset others because you don't want to upset your self. You are acting in bad faith, the taste of a bad infinity.

Because, you see, the alarming fact is that any realization of depth carries a terrible burden: Those who are allowed to see are simultaneously saddled with the obligation to communicate that vision in no uncertain terms. That is the bargain. You were allowed to see the truth under the agreement that you would communicate it to others (that is the ultimate meaning of the bodhisattva vow). And therefore, if you have seen, you simply must speak out. Speak out with compassion, or speak out with angry wisdom, or speak out with skillful means, but speak out you must.

This is truly a terrible burden, a horrible burden, because in any case there is no room for timidity. The fact that you might be wrong is simply no excuse: you might be right in your communication, and you might be wrong, but that doesn't matter. What does matter, as Kierkegaard so rudely reminded us, is that only by investing and speaking your vision with passion, can the truth, one way or another, finally penetrate the reluctance of the world. If you are right, or if you are wrong, it is only your passion that will force either to be discovered. It is your duty to promote that discovery—either way—and therefore it is your duty to speak your truth with whatever passion and courage you can find in your heart. You must shout, in whatever way you can.

The vulgar world is already shouting, and with such a raucous rancor that truer voices can scarcely be heard at all. The materialistic world is already full of advertisements and allure, screams of enticement and cries of commerce, wails of welcome and whoops of come hither. I don't mean to be harsh here, and we must honor all lesser engagements. Nonetheless, you must have noticed that the word "soul" is now the hottest item in bestselling book titles—but all "soul" really means, in most of these books, is simply the ego in drag. "Soul" has come to denote, in this feeding frenzy of translative grasping, not that which is timeless in you but that which most loudly thrashes around in time, and thus "care of the soul" incomprehensibly means nothing much more than focusing intensely on your ardently separate self. Likewise, "spiritual" is on everybody's lips, but usually all it really means is any intense egoic feeling, just as "heart" has come to mean any sincere sentiment of the self-contraction.

All of this, truly, is just the same ole translative game, dressed up and gone to town. Even that would be more than acceptable were it not for the alarming fact that all of that translative jockeying is aggressively called "transformation," when all it is, of course, is a new series of frisky translations. In other words, there seems to be, alas, a deep hypocrisy hidden in the game of taking any new translation and calling it the great transformation. And the world at large—East or West, North or South—is, and always has been, for the most part, perfectly deaf to this calamity.

And so, given the measure of your own authentic realization, you were actually thinking about gently whispering into the ear of that near-deaf world? No, my friend, you must shout. Shout from the heart of what you have seen, shout however you can.

But not indiscriminately. Let us proceed carefully with this transformative shout. Let small pockets of radically transformative spirituality, authentic spirituality, focus their efforts and transform their students. And let these pockets slowly, carefully, responsibly, humbly, begin to spread their influence, embracing an absolute tolerance for all views, but attempting nonetheless to advocate a true and authentic and integral spirituality—by example, by radiance, by obvious release, by unmistakable liberation. Let those pockets of transformation gently persuade the world and its reluctant selves, and challenge their legitimacy, and challenge their limiting translations, and offer an awakening in the face of the numbness that haunts the world at large.

Let it start right here, right now, with us—with you and with me—and with our commitment to breathe into infinity until infinity alone is the only statement that the world will recognize. Let a radical realization shine from our faces, and roar from our hearts, and thunder from our brains—this simple fact, this obvious fact: that you, in the very immediateness of your present awareness, are in fact the entire world, in all its frost and fever, in all its glories and its grace, in all its triumphs and its tears. You do not see the sun, you are the sun; you do not hear the rain, you are the rain; you do not feel the earth, you are the earth. And in that simple, clear, unmistakable regard, translation has ceased in all domains, and you have transformed into the very Heart of the Kosmos itself—and there, right there, very simply, very quietly, it is all undone.

Wonder and remorse will then be alien to you, and self and others will be alien to you, and outside and inside will have no meaning at all. And in that obvious shock of recognition—where my Master is my Self, and that Self is the Kosmos at large, and the Kosmos is my Soul—you will walk very gently into the fog of this world, and transform it entirely by doing nothing at all.

And then, and then, and only then—you will finally, clearly, carefully and with compassion, write on the tombstone of a self that never even existed: There is only Ati.

Ken Wilber is author of The Spectrum of Consciousness; Grace and Grit; Sex, Ecology, Spirituality; A Brief History of Everything; The Eye of Spirit and other books.